There is a great reset underway, but not the kind you might be thinking of. This one is a story of an over-indebted reserve country that is slowly going to be eaten up by debt and interest payments creating a debt doom loop with no way out other than for the Fed and Treasury to

come together and print our way out of it.

This post explores the fundamentals of why this is occurring and maps out what you can do to prepare yourself for such an outcome.

We begin by explain what it actually means when the Fed conducts monetary policy.

What happens when the Fed tightens monetary policy?

There’s a simplistic view of monetary policy and how it works, and then there’s how it actually works. To understand how it truly works, we need to start with the price of money in the economy. Think of the financial system as a set of building blocks that stack on top of each other that in general provide higher potential returns, but also more risk associated with it.

At the center of this financial system of building blocks is the US Treasury market and the yield curve. The yield curve represents the yield of US debt at different durations, or tenors.

The Federal Reserve has the ability to directly manipulate the yield at the short end of the curve through the interest rate it offers through inter-bank lending on the Federal Funds Rate (the rate banks can borrow between commercial banks), the discount window (the rate banks can borrow from the Fed), and the repo market/reverse repo market (markets where primary dealers can post collateral and receive cash, or park cash and receive a yield). The combination of these different mechanisms creates the Federal Funds Rate band - a 0.25% range where the Fed wants short term rates on the price of money to reside.

Through tweaking these different rates, the Fed directly controls the rate up to 1year maturity somewhat directly. This section of rates we consider as money markets.

From 2y up to 30y duration is what we consider to be capital market rates and the Fed does not have direct influence over these rates. They are primarily driven by longer-run economic expectations, inflation expectations, productivity, and supply/demand for longer duration assets.

Despite not being able to influence the long end directly, the Fed does attempt to influence it indirectly. It does this through two mechanisms: forward guidance (using their economic projections and longer run projections of fed policy to influence inflation/economic expectations), and influencing supply/demand dynamics through purchasing long duration assets (bonds and mortgage-backed securities) i.e QE, or letting their balance sheet of holdings roll off the balance sheet and expire without rolling the bonds, increasing the supply of bonds on the open market, i.e QT.

Generally speaking, QE is used to attempt to lower yields on the long end, increase inflation expectations, and as a signalling tool. Meanwhile, QT is used to let yields increase and decrease bank reserves within the commercial banking system. Both of these tools also have a secondary effect of affecting bank reserve levels within the commercial banking system which can affect lending capacity of banks.

One important nuance to understand about how monetary policy influences economic activity and the yield curve is that they are broad tools with very little granularity to them. When the Fed raises rates, they are attempting to make it more expensive for borrowers as interest expenses increases. However, it’s important to remember that the US government/Treasury is a borrower. Therefore, when rates increase across the board, the interest expenses for the Treasury also increase. Depending on how those interest expenses are funded, they can over time become somewhat stimulative. As an example, a 10yr bond that yielded 0.7% two years ago now yields 5% - that is a significant increase in income for the owner of the newly issued 5% bond vs the 0.7% one. What the Fed hopes is that this aggregate increase in rates slows down lending/borrowing enough to offset any form of stimulative potential that US Treasury debt holders may enjoy.

Treasury Issuance and the increasing deficits game + entitlements

With the above established, it’s now time to look at US government spending, entitlements, and financing deficits.

Think of the government budget much like an income statement for any typical business - you have revenues and expenses.

The government receives most of its income through tax receipts. The following shows the average tax income as well as long run projections as a % of GDP from the congressional budget office:

On the other side of the income statement is expenses, or outlays. They comprise the following and are projected as:

The difference between the revenues and the outlays creates the deficit (or surplus, if it is positive).

When tax receipts are not high enough to meet the obligations/entitlements/outlays, the US Treasury must issue debt to fund that government spending and auction bonds to the public market. As we can see, both the net interest outlays and the absolute deficit as a % of GDP are expected to increase over coming decades significantly. However, all other outlays are generally projected to trend somewhat flat. The reason for this expected deficit is what I call the financing conundrum and goes as followed:

The primary outlays from the government are somewhat set in stone and difficult to decrease for a multitude of reasons:

Social security: Somewhat essential to the livelihood of those not being able to make ends meet

Medicare/Medicaid: The US healthcare system is already struggling in terms of affordability and there’s little appetite from even hardline Republicans that were typically for decreased spending

Defense spending: No president or sitting party has ever or would ever decrease defense spending. As the largest military in the world and world reserve currency, the US defense budget is essential to the continued functioning of the global world order.

If any of these outlays were to decrease, we would call this austerity. Austerity is not a very popular platform for politicians to run on and is therefore rarely utilized.

With these outlays in stone, tax receipts need to at the very least cover these expenses and then try to chip away at interest expenses associated with the debt used to fund deficit spending. However, it’s projected for tax receipts to stay flat for the foreseeable future. The only reason they spiked in 2022 was due to a roaring stock market post-covid leading to higher capital gains and fiscal stimulus (stimmy checks were taxable)

Therefore, to fund the increase in interest expenses required on US debt, the Treasury needs to issue more debt to use that issuance to keep paying bondholders their coupons.

However, the Fed has been increasing interest rates which is making issuance more expensive for the Treasury. This means that the new debt the Treasury is issuing is leading to an increased net interest outlay in the expense tab for the government.

This increased net interest outlay is increasing the deficit for the government which means the Treasury then needs to issue even more debt to continue to fund obligations, all done at now even higher rates.

As well, as existing US bonds mature and need to be refinanced, they then need to be refinanced at these new higher rates. The following chart shows the maturity of existing US debt:

Most of this debt was issued at much lower interest rates and will now need to be refinanced at higher rates which will further increase the net interest outlays for the US government which only further increases the deficit.

This refinancing loop is at the core of why the Congressional Budget Office (a government institution) is so confidently projecting such significant deficits in the coming years.

To keep this refinancing loop afloat, multiple things need to keep occurring:

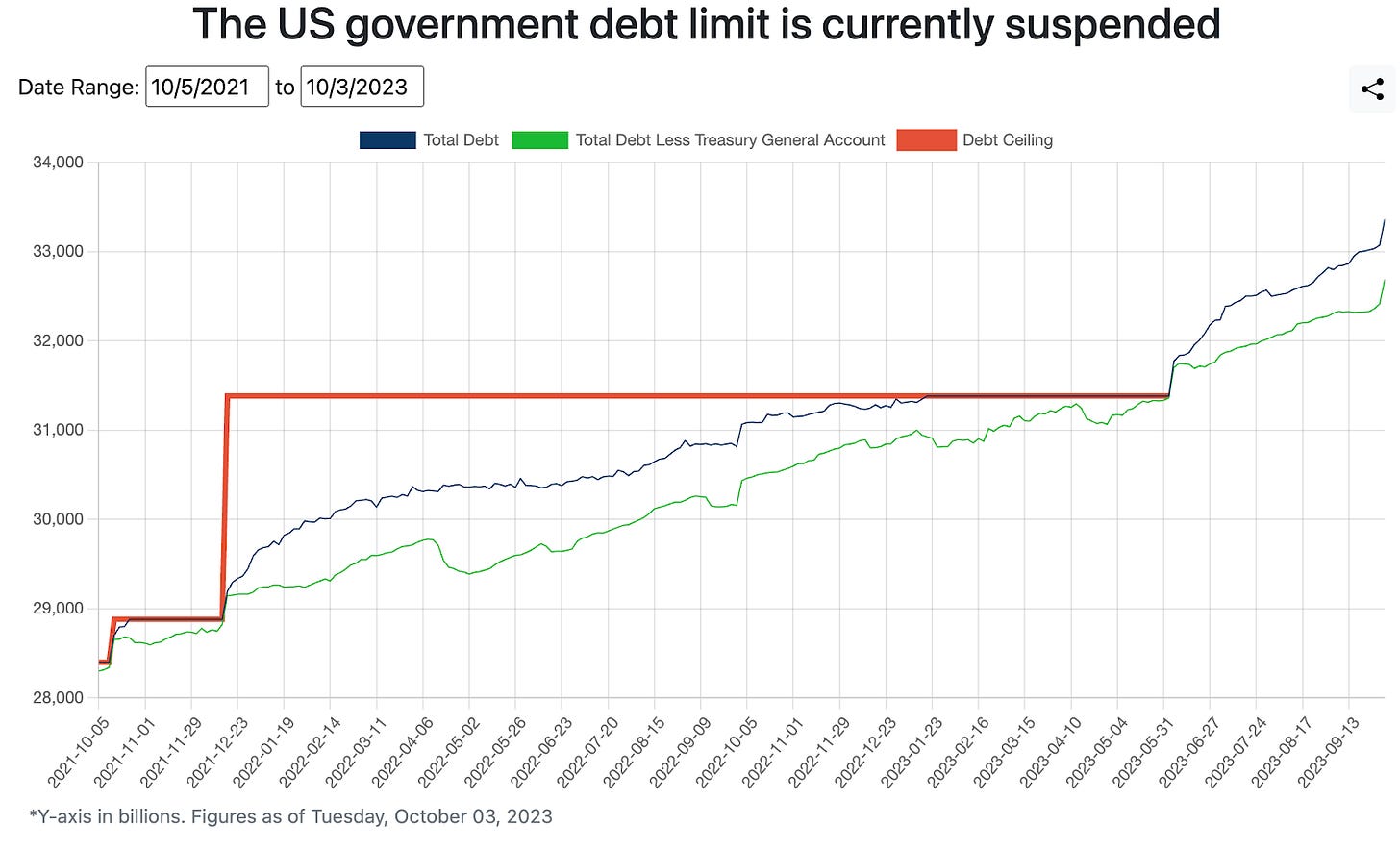

The debt ceiling needs to keep getting increased so the government can keep issuing more debt, otherwise the Treasury will not be able to provide interest payments on debt since tax receipts will remain flat.

Janet Yellen, the Secretary of the Treasury, alongside TBAC (the borrowing advisory committee that provides recommendations on lending for the government on a quarterly basis) need to strategically issue increasing amounts of debt at parts of the yield curve that have enough liquidity and demand to absorb the increase supply without leading to too-high of yields which would only make this refinancing loop even worse.

Who’s gonna buy the debt in a world of secular inflation

We now know a few things:

How monetary policy actually works and what parts of the yield curve the fed can directly control vs indirectly influence

Increases in interest rates can be stimulative when the yield on US debt increases while certain portions of consumer debt such as mortgages can remain fixed at historical lows

The US government is destined to experience a major budget deficit driven by increases in interest expenses due to the debt issuance feedback loop paired with the inability to cut entitlements due to the political nature of the decision

To fund that deficit gap the Treasury needs to issue increasingly more debt to roll the previous debt and fund increased interest expenses without spooking markets and letting yields get so high as to get out of control causing a non-linear outcome to interest payments across the economy.

With this framework in mind, we can now shift gears to exploring who will absorb all this upcoming and continued debt issuance.

First, let’s look at who have been the historical purchases of Treasuries, thanks to liquiditywiz.com:

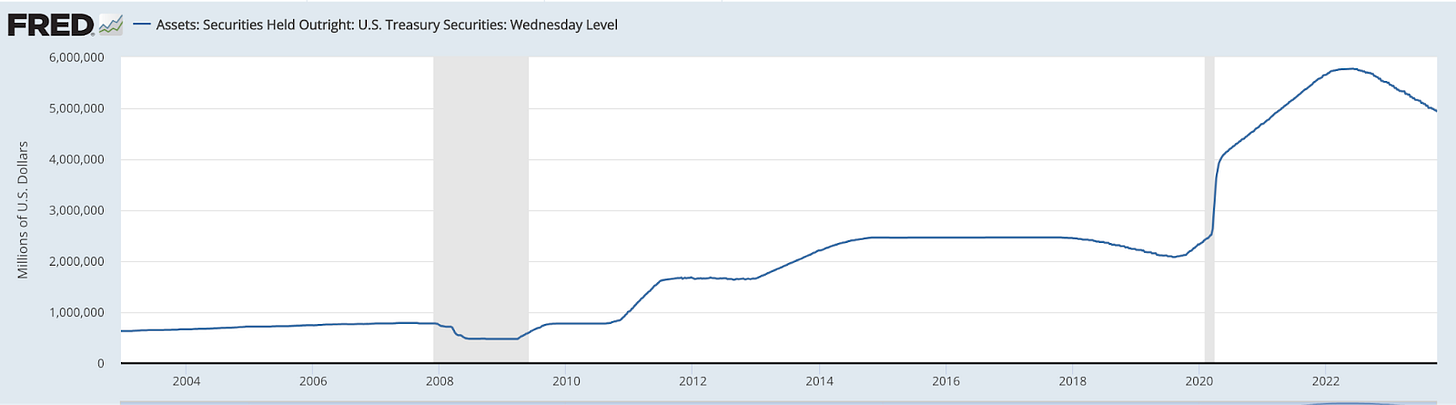

What we see is that both the Federal Reserve and Foreign Sovereigns such as central banks and sovereign wealth funds have not only stopped buying treasuries but have actually become net-sellers of US treasuries. As well, the Fed, which mostly amassed its bond portfolio through QE, is now trying to unwind that same portfolio through QT.

This leads to private investors such as hedge funds, banks, pension funds, individuals, and money market funds to be the marginal buyers of US debt at the moment. Let’s now explore how these marginal buyers can be examined through different parts of the yield curve so we can get an idea of where the market driving catalysts may reside.

Short end

The short end of the curve, what I’ve called the Money Market part of the curve, is primarily bought and sold by money market funds and is the most liquid market in the entire world. So liquid in fact that it is viewed effectively as a cash-like equivalent within GAAP accounting standards.

For the sake of creating a simplified framework, there are a couple key dynamics to understand demand for short end debt (called Tbills from here on out)

Opportunity cost for those that have $ within commercial banks and the yield they can receive there + the degree to which they have confidence in that bank and the associated FDIC insurance which only covers up to $250k. Recently, yields in money market funds (MMF) have been much better than commercial bank yields (banks cannot be profitable with an inverted yield curve since they borrow short and lend long, more on this in another post) so there has been a consistent outflow of bank deposits out of the commercial banking system and into MMF’s for the higher yield and no bank creditworthiness risk.

The Reverse Repo Facility is a special facility managed by the Fed that allows primary dealers (think commercial banks and MMF’s) to park cash at and receive a yield. The degree to which money flows in and out of the RRP is primarily driven by the spread between the RRP yield and the yield that can be received in short term Tbills:

Ever since the debt ceiling limit was moved higher, Treasury Secretary Yellen has been on a debt issuance spree to rebuild the Treasury General Account, which is effectively the spending account for the Treasury and is housed at the Fed. when the Treasury auctions off new debt, the cash goes here.

To fund this TGA rebuild, Yellen opted to primarily issue short term Tbills. The reason for this unlocks the key to what drives issuance on the short end of the curve.

At the beginning of the TGA rebuild, there was $2t in cash in the RRP, now $1.34t. This can be considered as sidelined liquidity that would be willing and able to move into short term Tbills if the yield on those Tbills increased enough to make them more attractive than the yield that could be gained at the RRP. Therefore, to entice this money out of RRP and to fund the TGA rebuild, Yellen issued a significant amount of the needed debt on the short end and managed to get the majority of that rebuild to be financed by the RRP.

What this shows us is that the RRP balance can be considered as standing guaranteed demand to absorb debt issuance through Tbills. Therefore, we can safely assume there’s another $1.34T in demand ready to absorb future debt issuance.

Though this is a lot of cash, it is only a short term solution and will very quickly end up at 0 as the debt issuance feedback loop continues long term. As well, there are a few more short term risks if Yellen were to entirely issue Tbills:

They need to consider the risk of spooking borrowers. If Yellen were to suddenly only start issuing on the short end, it might make long end owners think that they know there is an issue with liquidity on the long end and begin to sell their long duration bonds en-masse, making those yields surge higher and having cascading effects on things like 30yr mortgage rates which are priced off the 30yr bond.

There are established TBAC mandates and guidelines around the % of issued debt and its duration. Historically, they’ve targeted around a 20% portion of debt to be Tbill but already recently moved that limit higher to 22%. Pivoting to a major shift in this composition could cause significant bond market volatility.

The $1.34t in the RRP seems like a lot but compared the continuing march of debt rolling won’t last long at all and is only a very short term dampener and absorber of debt.

Long end

With all of this in mind, we can see that the Treasury cannot rely on entirely funding the deficit gap through issuing on the short end, and need to look at longer tenors, which Yellen and the TBAC are admitting to. Below is a chart showing the Treasury financing schedule for Q4 2023.

What we can see is a significant shift to longer tenors for issuance. Moreover, this amount of supply of debt being issued was much higher than anyone expected.

Ever since the TBAC announced issuance plans for the next quarter, yields on the long end of the curve have been exploding higher, leading to the popular ETF of long duration bonds TLT to be -11% since:

Many have speculated about what is currently causing the long end to surge like this:

As the US economy continues to remain resilient, those that purchased long duration bonds in expectation of hard landing/recession are capitulating as they now pivot to a soft landing consensus and are selling these bonds

The market is finally fully believing Powell that rates will be higher for much much longer leading to sustained higher rates into longer durations

Inflation is going to remain sticky for the next decade leading to a higher baseline inflation rate and therefore rates should be higher in the long end

Indeed, these possibilities are probably somewhat attributable to the rise in yields, but I strongly believe that they are not the primary driver of this price action and it entirely has to do with the lead up of this entire article:

Who is going to buy up all this debt if the key marginal and price-insensitive buyers have all disappeared?

This is the question that is beginning to worry the bond market. It is the same question that led to Moody to recently downgrade the US’s credit rating from AAA to AA.

Let’s explore who could be potential marginal buyers and where they currently stand:

The Federal Reserve: The Fed has been the most consistent and reliable price-insensitive purchaser of Treasury securities since 2008 through Quantitative Easing. QE involves a swap where the Fed purchases Treasuries from commercial banks and swaps them for central bank reserves. However, since QT began in 2022, the Fed is now no longer a buyer of Treasuries. Many think QT involves the outright selling of their bond holdings, but as it currently stands it simply pertains to the Fed letting a certain $ amount of bonds expire each month and to not re-roll that cash into more bonds. Simply put, this means the Fed is absolutely not purchasing any Treasuries and will not do so whilst inflation is above their policy goal. Even more, Chair Powell has hinted that they would be willing to cut Fed Funds Rates while still doing QT, something that has never happened before and showcases the commitment the Fed has to not wanting to pause QT unless something truly breaks. This means the Fed is not showing up to soak up long end bond issuance anytime soon.

Commercial banks: When commercial banks receive customer deposits, they retain them as US Treasuries, typically in the belly of the curve of 2y, 5y, and 10y. However, commercial banks are now filled to the brim with treasuries and wouldn’t become new buyers unless the Fed tweaked the SLR exemption which would be a policy change that would allow commercial banks to own more Treasuries without being impaired from a liquidity perspective.

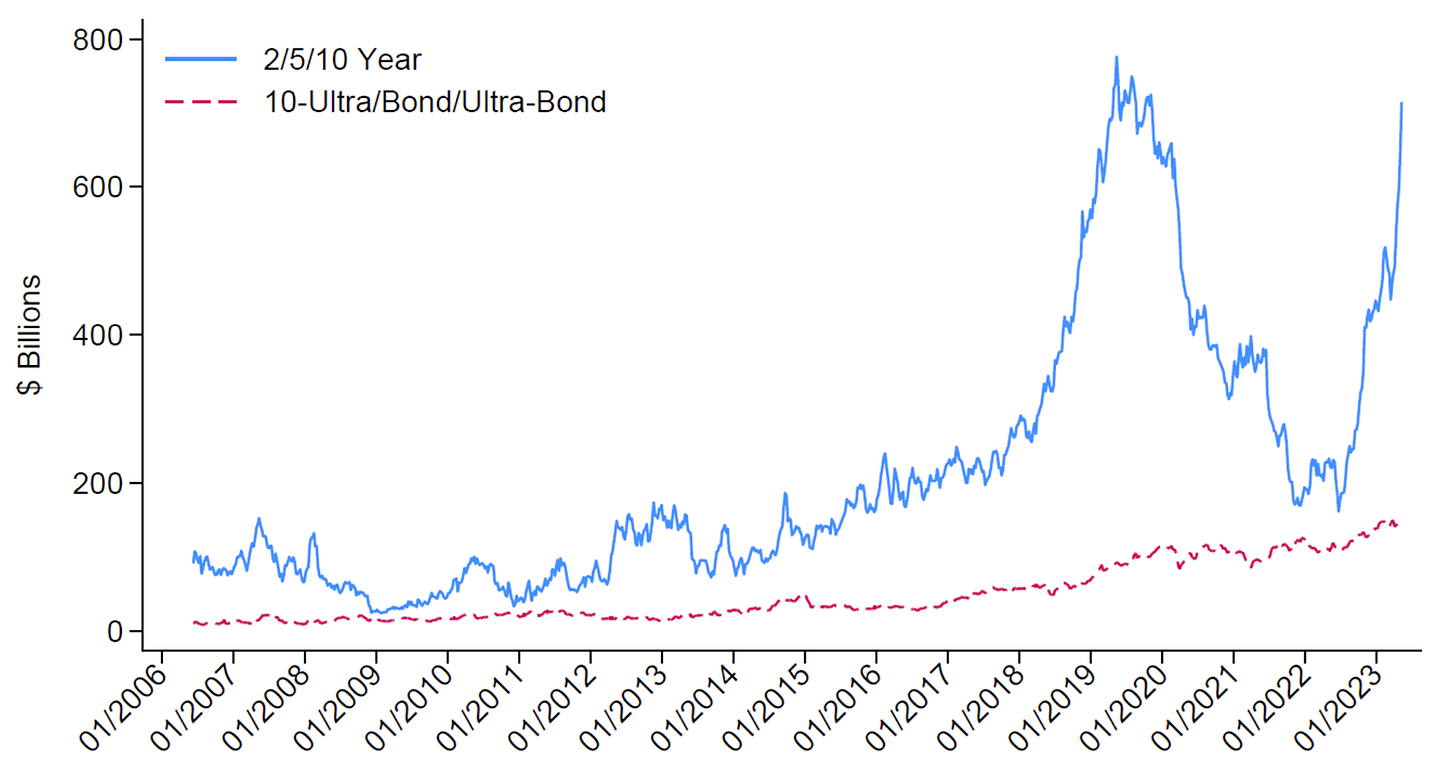

Hedge funds: Hedge funds are generally speculators within the Treasury landscape and one of the more popular methods that makes them a buyer of cash Treasuries (vs speculating on futures) is the basis trade where they short Treasury futures and long cash Treasuries and earn the positive carry between the two assets. Though we cannot see their physical Treasury holdings that easily, we can get a good look at their position sizing by seeing their CFTC Future short positioning. What we see is that we are now reaching a similar level to the last major basis trade cycle maxed out which implies that hedge funds are no longer a steady buyer of long duration bonds

Sovereign central banks/funds: There is a lot of debate around whether foreign sovereigns have become net-sellers of Treasuries or not. The ultimate debate resides around whether some countries such as Japan and China are having to sell their US dollar holdings to swap for their domestic currencies to defend them amidst a hawkish US policy stance that is harming their currencies. However, this argument is too uncertain but what we do know for certain is they are not buying more treasuries and clearly are not showing up as a consistent and price-insensitive marginal buyer.

Pension funds: Pension funds are probably the closest to an institutional bidder that we have on the long end at the moment. However, even with that, there is very little appetite when you look under the hood. Though it is paywalled, I highly recommend the work of Joseph Wang here who did the work of analyzing pension fund appetite for Treasuries can came to the conclusion they’re mostly maxed out: https://fedguy.com/slow-money/

Retail: And so, that leaves retail and individuals. Here, quantifiable data gets murky, but the best compass we can utilize to gauge this is opportunity cost. As yields on long duration assets rise, the yield that can be earned there will continue to make riskier assets with similar yields make less sense. This would then lead to individuals selling their riskier assets like equities to purchase bonds which have a higher yield with no credit risk and no real risk assuming they would hold to maturity.

With all of this in mind, it's clear there is no steady institutional bid for the long end of the Treasury curve and in light of increased issuance from the Treasury for the foreseeable future, long end bond market participants are now worrying about who will purchase this debt. The only real buyer that could show up is the Fed, but for that to happen they need the political cover of a recession or at least inflation below 2% to consider openly doing QE again.

That, or for the bond market to become so illiquid that the Treasury market would seize up to the point we see the long end cease to operate properly similarly to what happened in England last fall when the long end exploded higher and led to the Bank of England to go from discussing QT to doing a form of QE overnight to save the pension funds that were over-exposed to the move.

That said, before the Fed shows up to save the day on the long end, there are a few more tools that can be used by the Treasury/the Fed to attempt to manage the long end before giving in to outright QE, or all out Yield Curve Control (more on this in a minute):

Treasury buybacks: back in may, the Treasury announced they would begin doing treasury buybacks for the first time since 2000. This involves them issuing more liquid and “on the run” (i.e freshly issued debt) to then use to purchase “off the run” debt (older bonds that are less liquid). With ample demand on the short end, they could issue significant Tbills funded by the RRP to then purchase illiquid portions of the long end that could be the most prone to seizing up during illiquid market events

Operation twist: As what was done in 2012, the Fed could sell short term securities and purchase the same amount of long dated securities, called operation twist. This would be a way to raise the short end higher and lower the long end. That said, with the short end already so high, this option is somewhat unlikely.

BTFP Infinity: The BTFP, a facility launched in March during the regional banking crisis, is currently said to end next year and is so far only loan-based instead of outright purchases like QE is. That said, the Fed could lower the rate they offer loans at the BTFP to struggling holders of underwater long duration bonds to manage liquidity and selling of the assets.

These options only attempt to fix liquidity and do not provide what the market is signaling what it wants to see: a steady and consistent marginal buyer of long duration bonds.

So, what’s next?

For the Fed to show back up into being a participant on the long end, which as we have articulated above needs to happen otherwise long end yields risk eventually exploding to levels so high that they would spell economic armageddon, the Fed needs to hope for a recession or for inflation to come below 2% as soon as possible. Suddenly, it makes sense why they are so desperate to be so hawkish so quickly. Time is of the essence and every month where they cannot contain long end yields is more time where all that Treasury debt will get refinanced at higher rates.

YCC + QE Endgame

Eventually, a market breaking event will happen. Eventually, this recession will show up. And when it does, the Fed will once again come in guns blazing to purchase this debt, and so will individuals buying long end bonds for the recession trade. They simply need to because no one else will, aside from some small tweaks they can do through things like BTFP, Treasury buybacks, and SLR exemptions.

During the last crisis in 2020, the Fed effectively implemented QE infinity. They would purchase as many bonds as they needed to do stabilize markets. The next step would be for them to implement Yield Curve Control. Whereas QE is buying a certain amount of bonds at any price, YCC involves purchasing unlimited amounts of bonds at certain prices.

Similar to what the Bank of Japan does, the Fed could decide (either explicitly or implicitly) to purchase as many bonds as they would need to suppress yields at a certain level. They could decide that a 10yr bond any high than 5% would exacerbate the debt feedback loop to such a degree they would need to suppress the yield lower to stop that from happening.

Now, to do this, the Fed would need to create new $ to swap for those bonds. Government debt/bonds and the currency they are issued in are joined at the hip and one will always affect the other. Therefore, setting aside the endless debate that occurs about whether QE/YCC is actually money printing or not, the currency gets devalued. As more bonds are purchased, more currency is created to do so as central bank reserves. As a currency gets debased like this, assets that are denominated in this currency will generally go up since there is more currency chasing after the same amount of that asset/good, pushing up demand and therefore price.

What this all comes together to mean is that the currency becomes the exhaust valve for the Fed + Treasury to manage yields and keep them within a manageable level as they navigate to the other side.

What is that otherside?

It’s inflating the debt away so that the debt/gdp ratio of the US government which is currently at 135% (extremely high historically) down to something like 50% which is more manageable. Since the debt cannot be lowered, they need to run the economy hot and have a strong nominal GDP through inflation/debasement until this normalizes. During this period, however, significant monetary inflation is nearly guaranteed and significant economic inflation is highly likely as well whenever the Treasury is issuing money directly to citizens similar to the stimulus checks during the 2020 Pandemic.

Therefore, we need to find ourselves a life raft that performs well during this period of yield suppression and currency debasement. For me, that’s long duration equities such as tech stocks like Apple, and cryptocurrency assets - especially Bitcoin.

These are assets that can track this debasement and although it may look like the price is going up significantly and making you rich on a nominal basis, you are effectively just staying flat on a real basis as the currency gets debased. But with that in mind, it is up to you to structure a portfolio that can either keep up or outperform this upcoming debt doomloop that is slowly beginning.

In conclusion, let’s recap this doom loop:

The debt doom loop

Government entitlements are fixed high and austerity is politically untenable

The Fed hikes rates making rates expensive for Treasury to issue

High rates makes for lower tax receipts and a flatlined market means no capital gains for anyone either

Lower tax receipts increases the deficit at the same time that interest expenses are increasing due to higher rates on issuance and rolling over debt at higher rates

Treasury needs to issue more debt to cover the interest expenses caused by higher rates

Deficits keeps widening because of higher rates + more $ total debt issued

More debt issuance causes holders of debt to become worried about increasing deficits, at the same time that demand is remaining flat and supply up, making for higher yields

Higher yields means even higher interest payments

This repeats until a marginal buyer shows up

As explained above there’s no good marginal buyer right now willing to show up

If long end continues to explode higher demanding a buyer, markets will crash

Eventually the fed is the only real buyer of the long end through QE/YCC, but they’re still doing QT which is making matters worse so a lot needs to change for them to come in.

So how do you calm down bond holders? Yield curve control. Commit to a 10YR at say 5% and defend that level, and inflate the debt/gdp ratio lower over time

This weakens the USD as it becomes the exhaust valve, however all other currencies and central banks would be doing this at the same time so USD will have relative strength

This will lead to USD denominated assets to explode higher

If this loop continues, we could see significant monetary debasement

Own bitcoin and other long duration assets to protect yourself. I.e, BTC to $500k but USD worthless

Eventually this monetary inflation will lead to exploding GDP growth making for debt/gdp ratio to be reset

This is the great reset. Own assets that make it through this reset and you will survive.

> This weakens the USD as it becomes the exhaust valve, however all other currencies and central banks would be doing this at the same time so USD will have relative strength

why do all other currencies + cbs also have to start doing YCC?

Great post. Thanks.